Singing Brahms's German Requiem -- for 71 immigrant families and their issue.

I sing with the Milwaukee Symphony Chorus, and we are in the

middle of an inspiring concert week, performing the Brahms German Requiem. Last

night, following a grueling week of fabulous rehearsals, we opened. We perform

again this evening and tomorrow afternoon.

Today I am so very tired. I had planned to post today a

well-reasoned and researched, and (hopefully) thoughtful piece about what

Brahms’s Requiem says to me, as my family’s historian. Then I thought it was

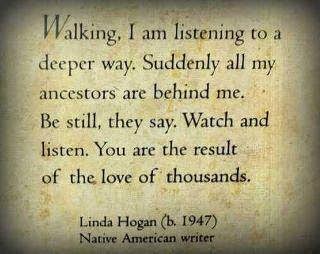

impossible, since I’ve been too wiped to write anything. But a photo posted by a Facebook

friend (see right) told me that, tired though I may be, I had something to say…now… Inartful

as it may be, here goes.

Brahms’s German Requiem has special meaning to every chorister who sings it.

We have all lost a loved one, of course, so any requiem would be meaningful.

But this requiem is considered a “humanist” requiem, unlike the Catholic mass

requiems created by the likes of Mozart and Verdi. They are incredible works, but

use the traditional Latin text. Although Brahms’s text is also from the Christian

Bible – Martin Luther’s version – its focus is on comfort rather than fire and

brimstone.

Why is this post showing up on my Time With My Ancestors

blog page? Because religion has played a fascinating role in my family tree. From

the time I first began building on my father’s family research, I have been

drawn to the role religious conflict played in how my ancestors came to

America, where they settled, what they did when they settled, and what they

passed on to their children.

I have identified 71 immigrant families in my family tree.

The first came to New England in 1624 and the last came to America in 1892. Here is link to my pretty complete immigrant list. I married an immigrant, so my

daughter’s tree covers a greater span and her list has 72 immigrants.

I have Puritans in my tree, so from the beginning my

immigrant ancestors didn’t “go with the flow” of the religion of their day. One

of my dear friends says that I come from a long line of “protestants”

(protestors) and she (and I) see in me the same attributes.

Since my immigrant ancestors came over the pond, there has

been much faith. And much religion. And much religious discontent. One

ancestress born of Puritans disliked going to church and was quite vocal about

it. That plus other questionable activity eventually led to her 1692 conviction

as a witch in Fairfield, Connecticut. She was trussed and dunked and floated

like a cork. Yup, she was definitely a witch. She later got off on a

technicality and returned to the community that convicted her. (That must have

been fun.) Another ancestress was sexually abused as a child in New Haven. Her

molester was hung. Because she had been corrupted she was publicly whipped. I

guess the Puritan judges thought they could beat the devil out of her somehow.

(Yes, New Haven court records from 1665 are extant and a 19th

century transcription can be viewed online. But not all of this particular

trial was transcribed—parts were seen as unfit for print.)

My Swedish Baptists fled their homeland in the mid-19th

Century. At that time, the Swedish state church was Lutheranism. Because

Baptists believe in adult baptism by submersion, they were easy to find.

Lutheran ministers would force baptism on children whose parents didn’t want

it. My Swedish ancestors were baptized as adults in rivers under bridges in the

dark of night. That way they were less likely to be accused of treason or stoned

by their neighbors. They eventually gave it all up and came to America, land of

religious tolerance.

Some Dutch and English ancestors ended up in New Amsterdam

in the mid-1600s. If you aren’t familiar with this pretty “open” society, it is

fascinating. New Amsterdam was a real frontier town, filled with diverse

peoples and general acceptance of the same. Some of my English ancestors ended

up there after having been driven out of the more staid New England colonies. I

also have a French Huguenot who ended up there.

My Norwegian immigrants came to America at the end of the 19th

century. They were Lutherans. To be accepted as a successful businessman in his

new American home town, my great-grandfather joined the Masons. When he and his

family were traveling, my grandmother was unexpected born prematurely. She was

so small they put her in a little box they set close to a hearth to keep her

warm. They thought she would die, and called for a Lutheran minister to baptize

her. When he arrived and saw my great-grandfather’s Masonic ring he refused to

baptize my grandmother. My great grandparents became Episcopalians on the spot,

and never returned to the faith of their homeland.

One of my ancestors graduated from Harvard in 1667. He would

have been there at the time of the Indian School, written about in the

fascinating novel Caleb’s Crossing. I suspect the novelist is right, and that

the New England school boys didn’t treat their Native American classmates well.

This particular ancestor went on to marry one of the richest girls in the New

Haven area, and was one of the earliest ministers of Elizabethtown, New Jersey.

He died of a stroke one Sunday, as he was preaching about the heresy of other

religions. He owned both Native American and African slaves.

I have lots of ancestors who settled in New England in the

17th century. It was, at the time, primarily a theocracy. [Here’s

where some scholarly writing with citations to on my research would help, but

no time for that now—agree or disagree with me as you wish!] Even though they

were all “Puritans,” for the most part my ancestors didn’t seem to get along

with their neighbors’ religious views. The folks who settled in Cambridge,

Massachusetts in the 1630s (including William Pantry, who built a home that

later became the first Harvard College building) didn’t stay long. They grew

discontented and traveled with their minister Thomas Hooker, so they could

found yet another town—Hartford, Connecticut. In fact, I have been known to say

that my ancestors were such religious malcontents that they never stayed in one

town long. Instead, they seem to have founded every little town in the state of

Connecticut!

Moving forward a century or two, one of my ancestral

families came from Prussia (Germany didn’t exist at the time), and ended up

settling in Milwaukee County, Wisconsin in the 1850s. They were founding members

of the Wisconsin Lutheran Synod. I moved to Milwaukee in 1981. I only learned of

this immigrant family in 2010 or thereabouts, and have since then found their Lutheran

graves at St. John’s Church in Oak Creek. One of the sons of this immigrant

family moved to Minnesota, and his son married my grandmother (the one who was

born so small and the minister wouldn’t baptize her). Their marriage was a

disaster, and my grandparents ended up getting a divorce. So sometime in the

1930s my mother was told that her mother was damned for eternity because she

had been divorced. Needless to say, that did not sit well with my mother, who

spent the rest of her life “searching for” rather than necessarily “believing”

in any one faith.

My father, on the other hand, descended from the cranky New

Englanders and the Swedish Baptists. The New Englanders ended up in upstate New

York just in time for the Erie Canal, Women’s Rights, the Underground Railroad,

Free Love communities, the founding of the Mormon Church, and Baptist and

Methodist revivals. Upstate New York in the first half of the 19th

century was a hot bed of activity, religious and otherwise. [Someday I’ll write

much more about that!] My New Englanders/New Yorkers became Baptists, and one

of their female clan members married a Swedish Baptist who happened to be a

minister. That Baptist minister was my grandfather, and at the time of his

sudden death in the 1930s he was the head of the American Baptist Church of

Illinois.

SO, my constantly searching mother with a damned mother married

my son of the leader of the American Baptist Church of Illinois father who, to

his death, believed when he died he would see his parents and other loved ones

who passed before him. They had two children, myself and my sister, and the

game of religious discontent continued. (My blog "photo" is my parents' wedding picture.)

My parents both believed we should be brought up in a faith

community. (I believe this as well, challenging as it might be). My sister was

christened a Presbyterian because my mother’s brother had become a Presbyterian

minister/chaplain during World War II. I was christened a Lutheran (I think)

because we were Lutherans at the time. My sister and I were both confirmed

Methodists. At one time or another we attended the Baptist, Lutheran, Methodist

and Unitarian churches. The rule was: if my father enjoyed the sermons,

eventually my mother couldn’t handle them; if my mother enjoyed the sermons,

eventually the minister got fired. Every Sunday we attended one church or

another, and afterward my sister and I would sit in the backseat of the car

while my father drove and my parents argued about the sermon. Then we would go

to Bridgeman’s for ice cream. The fact that I still love ice cream is a

testament to my parents—no matter their feelings about religion, they loved and

respected each other, and I never felt the arguments were unkind or unjust. But

they were very interesting!

Since I can remember I have been interested in questions of

faith and religion. My mother’s searching led to my own brush with damnation.

When I was in Sunday school at a Methodist church, I mentioned that my mother

was not a Christian. I can still see the teacher and the table with a dozen or

so of my classmates, when she (the Sunday school teacher) told me my mother was

damned for eternity. Soon thereafter I quit “believing” and started “searching”

instead. No doubt this particular Sunday school teacher would have damned me as

well….

(Side Bar: I remember when my own daughter was five and I

was driving with her on County Line C in Cedarburg, WI. She told me she had seen

Jesus and believed in him. I got so angry I had to pull to the side of the

road, where I lectured her about Christianity and its exclusivity clause. I

finally calmed down and told her I was fine with her being a Christian, depending

on what kind of Christian she was. Her response was to say “I’ll be whatever

you want me to be, mommy!” Goodness, she was only five – the things we do to

our children. She has since recovered and is on her own search….)

Despite my background, or maybe because of it, at one time I

hoped to become a minister myself (don’t ask me what faith, I never got that

far). I do believe in faith and the positive role it can play in lives. And I

am generally fascinated with questions of faith. I went to a conservative

Lutheran college because of its music program. I dropped out of music my

freshman year because we spent a lot of time singing in what I call “an oh so

Lutheran way.” When my freshman classmates found out I wasn’t a Christian, they

took turns trying to convert me. At first it was fun. It is hard for one person

to convince another to believe—it is of course a “leap of faith” – and I used

my experience to hone my debating skills. Many a girl in my dorm ended an

evening in tears when I could not be swayed. Eventually this conversion process

seemed not only cruel but also became tiresome and time-consuming. From then

on, I would simply say that perhaps I did believe…that seemed to give the girls

comfort and me more time for studies.

Abandoning music, I took up student government instead. I dropped

that toward the end of my undergraduate career, when a committee I was on—to

choose the next student newspaper editor—refused to select the person I felt

most capable, SOLELY because he was an atheist. My personal view was that if

there was a role for an atheist at the school, it was in the Third Estate.

Still, religion intrigued me. In college I tried for a

Rockefeller grant, to go to divinity school. I made it to the finals and then

got shot down. But later I received a call from a conservative Baptist seminary

in Illinois, who wanted to give me a full ride. “Why,” I said, knowing I was

far from a conservative Baptist! “We think you would shake things up here a

bit, and we’d like to see that.” Oh my. Unfortunately (or fortunately) I had

already accepted another job at the time, so I didn’t go to Illinois to join my

Baptist ancestor in his faith.

But by now you surely see a pattern…. I clearly take after

my cantankerous puritan ancestors, and am a true “protestant”!

I eventually married, into a Zoroastrian family. My husband

is pure Persian. His people were conquered by Alexander the Great (Alexander

the Terrible my uncle-in-law calls him). Then, during the time of Mohammad,

they were told to convert to Islam or die. [This is NOT a diatribe against

Islam—from where I sit lots of religions have done nasty things, and we could

cite many instances of religion gone amuck – the Spanish Inquisition, the

Crusades, Hitler’s Aryans, etc. etc.] Instead of converting (or dying), my

husband’s Zoroastrian ancestors moved to India, where they were allowed to

settle as long as they didn’t intermarry or convert others.

Why am I not a Zoroastrian? Why are there no Zoroastrian

temples in Milwaukee? It is a dying faith. Unfortunate. To my knowledge, the

Zoroastrians never persecuted others, which makes them perhaps one of the “better”

religions. But they do educate their young, and to this day they do not allow

conversion. Educated young travel and marry outside of their faith… a recipe sure to kill off a religion, no matter how noble.

My husband was born in India. Before the Second World War,

India and Pakistan were one country. The primary faiths were Hindu and Muslim.

The country was partitioned after the War, in the name of religion. Hindus were

forced to leave what is now Pakistan, and Muslims were forced to leave what is

now India. It was not a pleasant partition. 14 million people were displaced. Yes,

14,000,000—it is the largest mass migration in human history. Many died. For

example, Muslims would fill a train leaving India for Pakistan, the train would

be ambushed, the passengers would all be killed, and words to the effect of

“here are your Muslims” would be written on the train in blood before sending the

train filled with dead bodies on to Pakistan. Hindus traveling to India fared

no better. My mother-in-law worked in the resettlement camps and saw the

devastation of “The Partition” first hand. Few Americans know of this act of

horror in the name of religion. But many in the region remember.

So here I am today. I do not go to church regularly. But

often when I travel in search of my dead relatives, I attend a church in the

area, one of their particular faith. I have heard wonderful sermons and met wonderful

people.

What does this have to do with Brahms? Depending on whom you

ask, Johannes Brahms was either an atheist or an agnostic. He did not write his

requiem for a particular church, so was not constrained to the “standard

requiem format.” He clearly saw the value of faith, yet had “issues” with

religion. I am not an atheist. I am a person of faith, but I’m not always keen

on religion. And through my family research I have come to discover that I am

not the first in my long family tree to have “issues” with religion. That’s

why, I think, I like the Brahms Requiem more than the others. It is the text that draws me.

Whatever may draw you to this piece of music, I suggest you

give it a listen. I also suspect that in your family tree there may be people

of faiths different than your own. That is especially true here in America,

land of immigrants. That’s why our revolutionary forefathers determined that

church and state had to be kept separate. So we could all get along…..

End note: I apologize for not including

citations in this text. If it were a Wiki page it would be full of “citations

needed”! I also apologize for any shortcomings in writing. It is indeed a first

draft. Finally, I mean not to offend any person of faith or religion. I simply

write of my own experiences, and of those in my family who went before me. I

plan to someday return to this blog and clean it up, adding citations and links

and improving the text. For now, this is what I have. Instead of napping I have

written. Hopefully my words will give me an extra boost of inspiration tonight,

when I sing the text of Brahms’s Requiem in honor of all 71 immigrant families on

my list, and the people that followed, all of whom helped make me who I am

today.