The Pequot Museum

On a recent trip to New England I had a chance to visit the Mashantucket Pequot Museum & Research Center. Located near Mystic, Connecticut, the Pequot Museum is fabulous in detail and display, and tells the story of the Mashantucket (Western) Pequots in an entertaining and informative way. A visit begins in a great hall, where lifelike mannequins of Pequot warriors are found traveling the Connecticut River. Visitors then descend downward, first on a ramp, then on an escalator surrounded by walls that look like ice. Cold air resonates from the depths below. At the base of the escalator Pequot life during the Ice Age is on display, and visitors can hear native peoples' origin stories.

And from there, visitors travel through time, beginning at the beginning and ending in the now.

|

| Exhibits are close and beautifully crafted |

Especially intriguing to me was my walk through a 16th

century Pequot Village. It is filled with realistic dioramas. No barriers –

just a “please stay on the path” request. A visitor has an inside view of native life prior to the arrival of European settlers in the early 17th

century.

As one walks through the village, a large picture of a ship looms from a distance at the far side, a reminder that

Europeans will soon arrive. And with that arrival, Pequot life is changed forever. Trade begins, and the Pequots' trading skills make them one of the richest and most powerful of the native tribes. But soon disputes arise, and war follows.

|

| In addition to a map of the Village, visitors receive a free audio tour to use while exploring 16th century Pequot life |

Visitors follow the timeline from the first European settlers to the conflict that followed. They can watch short films, where the Dutch, English,

and Pequot each tell their side of the story, and then watch the graphic and powerful

film “Witness”, which tells the tale of the Pequot War through the eyes of a

young Pequot boy. In this film, visitors see the Pequot nation destroyed in a massacre.

The Massacre at Mystic and its Aftermath

The culmination of the Pequot War occurred in 1637, when Mistick Fort, a

palisade housing most of the Nation, was burned, and the men, women, and

children inside perished in the flames. It was a disaster for the Pequot Nation. Those who managed to escape were later captured and sold into slavery. The conflict is considered so critical that when the History Channel produced a series called "Ten Days That Unexpectedly Changed America," the Massacre at Mystic was included on the list. Some scholars believe the event changed the relationship between native peoples and Europeans, and set a process for taking native lands by wholesale slaughter of their people.

|

| From Captain John Underhill, a woodcut print depicting a birds-eyes view of the Battle of Mistick Fort, May 1637 |

Like

many conflicts between European settlers and native peoples, the Pequot War was caused by misunderstanding. And lack of respect. And greed. And fear. Other tribes joined the Europeans, for their own purposes. Was this war inevitable? Perhaps. Did it end nobly? Not if one thinks the wholesale killing of innocents is wrong. The Puritans, however, believed God was on their side, and celebrated , believing God meant them to annihilate this wealthy tribe. Unrepentant accounts of the battle were

published by its English participants, including the leader of the pack, John Mason. His story is very different from the Pequot story told in the film "Witness."

In the end, the Pequots did not die. Visitors to the

Museum see enslaved Pequots, Pequots living in farming communities, and later

in trailer parks and on a reservation. Pequot tribal members invested in economic ventures and instituted legal action to

recover illegally seized land. In 1986, the Western Pequots built the Foxwoods Resort Casino, the first Indian gaming casino in America. The Nation also created the

Mashantucket Pequot Museum and Research Center. Click HERE to read the history of the Mashantucket (Western) Pequot Nation.

The Museum does not treat the European colonists with disdain. Rather, it teaches understanding and tolerance, presenting

many viewpoints. It also brings today’s Mashantucket Pequot Nation to life. I saw museum quality wampum, and watched a video of an artist

creating wampum from shells, and turning that wampum into bracelets. And as my

visit ended, I was tempted to buy a bit of wampum myself in the museum store!

The Pequot War – Yes, My Relatives Were There

|

| From the film "Witness" |

After visiting the Pequot Museum, I wondered about the two dead relatives of mine who had been involved in the conflict. The first of these was Nathaniel Merriman (1613-1693). Merriman’s descendants left a rich accounting of his life in England old and new, and his service in the conflict is clear. His story I leave for another day.

Deacon Richard Goodman (1609-1676)

It was the second, Richard Goodman, who most intrigued me after my visit to the Pequot Museum. He is relatively unknown to me. Born in England in 1609, he owned land on “Cowyard Lane” in Cambridge, Massachusetts in 1633, and was mentioned in an earlier post about my family’s ties to Harvard. In addition to his role in Cambridge's history, he was a founder of Hartford, Connecticut, and Hadley, Massachusetts and was killed in Hadley in 1667, during King Philip's War.

|

| Hadley, MA Vital Records |

Visiting the Museum had prompted me to dig into a different setting for Goodman -- the

Pequot War. I found reference to service in the War by browsing through the records of the various known ancestors who were

in New England at the time. I started with Robert Charles Anderson’s Great Migration series, the best resource for the study of New England's earliest colonists available today. According to Anderson, Goodman was in the War, as proven by the fact that he owned land in

Hartford’s “Soldiers Field” (GM

Vol II p 787).

Follow the Source

Digging Deep

Anderson’s work is meticulous and an excellent resource, and every statement he makes is sourced. I went to his source, the “Original distribution of the lands in Hartford among the settlers, 1639” (CT Historical Society 1912, ed. Bates), which I found online. It listed many parcels owned by Goodman, including these:

|

| "Original Distribution" at p 84 (brackets show original record pages) |

I reviewed James Shepard’s “Connecticut Soldiers in the Pequot War” (1913), which can be read online. Shepard's entry on Goodman (page 16) read “Enlisted from Hartford (Parker). Had a lot in Soldiers Field.” There was that blasted field again, which seemed to be a code word for “massacred native peoples in 1637.”

In Shepard I found a deeper reference, though, to one Francis Parker, who had read a paper called “The Soldiers Field” before the Connecticut State Historical Society 5 February 1889. Mr. Shepard had very kindly told his readers that a manuscript of Parker’s paper was located at the Connecticut Historical Society. I could not, however, find it online, so I kept looking elsewhere.

|

| Hartford Founders Monument |

Where was the Pequot War? Nowhere. Going back further, I found Sylvester Judd’s “History of Hadley” (1863), which lists the founders of Hadley, and provides Goodman’s biography at page 499. Again, no Pequot War reference. Boltwood’s

“Genealogies of Hadley Families” (Northampton 1862) also failed to mention the

Pequot War in Goodman’s entry (page 59).

Normally, documents written closest to an event are the most trustworthy. These early documents did not mention service by Goodman. What gives – did he or did he not participate in the Pequot War?

Clearly, something had happened between 1886, when no one was connecting Goodman to the Pequot War, and 1912, when everyone was. And the later sources kept pointing me to a place in Ancient Hartford called “The Soldiers Field."

Normally, documents written closest to an event are the most trustworthy. These early documents did not mention service by Goodman. What gives – did he or did he not participate in the Pequot War?

Clearly, something had happened between 1886, when no one was connecting Goodman to the Pequot War, and 1912, when everyone was. And the later sources kept pointing me to a place in Ancient Hartford called “The Soldiers Field."

The Connecticut Historical Society

|

| Connecticut Historical Society, Hartford, CT |

The Land Puzzle

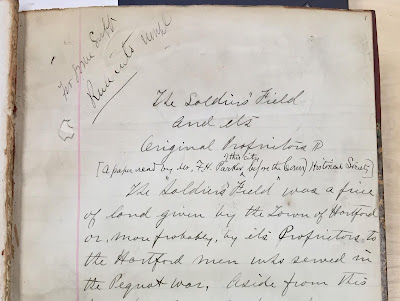

Parker’s handwritten manuscript (dated 4 Jan 1889) begins …. “The Soldiers Field was a piece of land given by the Town of Hartford, or more probably, by its Proprietors, to the Hartford men who served in the Pequot War.”

Parker goes on to say that there were few records left from those days, making it difficult to determine who owned what. But, using the original land records for Hartford (the Original Distribution list cited by Anderson), Parker meticulously rebuilt the Soldiers Field rood by rood. He proved who owned what and how they came to own it.

Parker acknowledged (at page 8) that some of the original holders of land in the field were not included in the accepted list of Pequot Soldiers. He too was well aware that there were sources that did not recognize Goodman's service. But he disputed those sources, and proved that the “evidence contained in the Book of Distribution clearly warrants the inclusion of their names.” A lawyer by trade, Parker nicely built the case that Richard Goodman had received a grant of land in Soldiers Field, and indeed served in the Pequot War.

There you have it.

I value the work of the Parkers of this world. He proved parts of history, and left a record of his proof. I also value the historical societies of the world, which house precious manuscripts, and remind us that sometimes you cannot find the answers on the internet, but instead you just have to go there.

Why Do I Care?

I admit, I sometimes wonder. Why do I care if

Goodman participated in the Pequot War? He was a wealthy colonist and a Puritan deacon. Whether

he grabbed his musket or not, he would have favored the fight.

Why did I want to go to the deepest source I could find? That is an easier question to answer. After finding conflicting data, I had a question. And when I have a question about American

history, I usually want an answer. I am consistently curious.

Query: Why did Richard Goodman move from Cambridge to Hartford and

then again to Hadley? Why did his wife Mary (Terry) Goodman move to Deerfield

after he died? What other dead relatives do I have in Hadley and Deerfield?

I know the answer to all but one of these questions – I have no idea why Mary Terry Goodman moved to Deerfield, although I suspect she had family there. But I will find out. Because I want to know.

|

| No headstone for Goodman remains, but I found this in the Old Hadley Cemetery |

I know the answer to all but one of these questions – I have no idea why Mary Terry Goodman moved to Deerfield, although I suspect she had family there. But I will find out. Because I want to know.

A Closing Thought on History

|

| "Lion Gardiner in the Pequot War" by Charles Reinhart (1890) |

History changes over time. The same facts are told and retold in a different way. The teller of the tale is always biased, and although each may tell "truth" as the teller knows it, bias affects the way the story is told. It also affects the way it is heard. As is the case with all news, it is best to read multiple reputable sources to get as close to the truth as one can.

When I visited the Pequot Museum, it had a special exhibit that dealt with “implicit bias.” We all have it. And although none of us can see it in ourselves, it affects everything we say and do. If you are interested, you can test your implicit bias at "Project Implicit", created by Harvard University and available online. Beware, you may not like what you learn. But, as the Southern Poverty Law Center aptly notes, "Your willingness to examine your own possible biases is an important step in understanding the roots of stereotypes and prejudice in our society."

If the Pequot War interests you, take a look at the

description of the war on the website of the Society of the Colonial Wars of the State of Connecticut. Compare it to the description on the Pequot Museum's website. Watch the History Channel's version. This will give you three perspectives on the War, four if you count my very brief recitation.

Never forget, history changes over time. It is also a story told by the teller.

Richard Goodman, this one’s for you.

The Mashantucket Pequot Museum & Research Center is a 308,000 square foot complex nestled in the woods near Mystic, Connecticut. Two of its five levels are underground, and the exterior space features a farmstead and other green spaces. The mission of the Museum is "to further knowledge and understanding of the richness and diversity of the indigenous cultures and societies of the United States and Canada." Explore the Center's guides HERE.